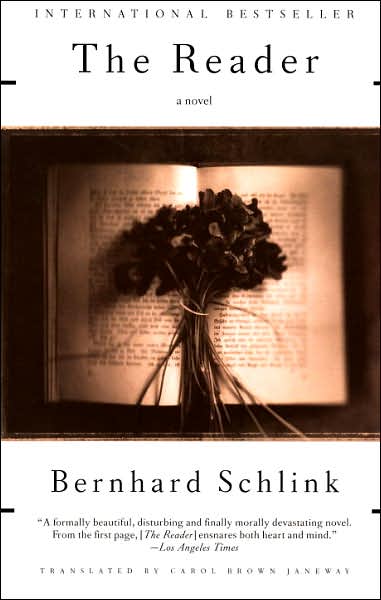

German author Bernhard Schlink’s 1995 novel The Reader is a tour de force character study that weaves questions of guilt, truth, and evil together with spare, beautiful prose. In 1959, fifteen-year-old German schoolboy Michael Berg has a five-month affair with thirty-six-year-old streetcar conductor Hanna Schmitz, is abandoned by her, and encounters her again by chance seven years later in a courtroom, where he is observing a trial for a law school seminar—and she is being tried for a war crime.

German author Bernhard Schlink’s 1995 novel The Reader is a tour de force character study that weaves questions of guilt, truth, and evil together with spare, beautiful prose. In 1959, fifteen-year-old German schoolboy Michael Berg has a five-month affair with thirty-six-year-old streetcar conductor Hanna Schmitz, is abandoned by her, and encounters her again by chance seven years later in a courtroom, where he is observing a trial for a law school seminar—and she is being tried for a war crime.A fast read, the text is full of striking images of eroticism, nature, and tenderness. Hanna is a strong physical presence, vividly described and by turns tender and physically abusive, and she proves to be just as strong an emotional presence for Michael after she is gone. Hanna strongly contrasts Michael, who is cerebral, analytical, and vulnerable to her strength of personality, yet she herself is a walking contradiction. Her tenderness is paired with coldness; her strength is paired with her own remarkable vulnerability; her care for him upon their first meeting, when he vomits in the street at the start of a case of hepatitis, is sudden, brusque, “almost an assault,” yet she embraces him when he cries. She primarily calls Michael “Kid,” and she often plays a mothering role in their encounters, bathing being the introduction and coda of their affair, but this tenderness does not change the fact that she is molesting a fifteen-year-old boy. Most troubling is Hanna’s strange combination of strength and weakness.

Michael learns during the trial that Hanna was an SS guard at Auschwitz and another concentration camp during the war and that during a journey to move many women prisoners, a church holding the prisoners had caught fire during a bombing, and Hanna and the other guards had left the church locked while it burned. Hanna explains that she did this because she and the few other guards present would not have been able to control the prisoners when they flooded out of the fire: “We couldn’t just let them escape!” Her explanations destroy her case.

Accountability and decision-making seem foreign to Hanna. She is an example of Hannah Arendt’s “banality of evil,” and, though a strong presence, she is ultimately weak because she drifts from one situation to another as if she has no choice in the matter—and yet we know, once we know her personal secret, which I will not reveal, that she did have another choice; but she dismissed it out of pride. At the age of twenty-one, she voluntarily joined the SS after being offered a job as a foreman at Siemens, the factory at which she worked. For Hanna, hiding her secret comes above making moral decisions. When questioned about her involvement in selecting prisoners in the camps to be put to death, she asks the judge, not in defiance, but in earnest, “I … I mean … so what would you have done?” Further along in this questioning, she asks aloud, “So should I have … should I have not … should I not have signed up at Siemens?” When questioned about her decision not to unlock the church doors, she again asks the judge, “What would you have done?” There is a strange virtue in her honestly seeking right answers to what she should have done. But it is disturbing that these questions are only coming now, years after the horrific facts.

Hanna remains a mystery throughout the novel, and her actions always leave Michael alone to pick up the pieces, first when she leaves town without an explanation, then at the end of the trial, and again at the end of her life. Yet her apparent cruelty is tempered with the true affection she felt for Michael after they parted and her desire to learn as much as possible about the Holocaust and its victims, both evidenced by the possessions in her prison cell. Further, she claims to be haunted nightly by the ghosts of her past. The puzzle of The Reader is whether Hanna is a monster or a sympathetic character. This question bonds us to our narrator, Michael, who spends most of his life enduring the same conflict, consciously and subconsciously.

Schlink's novel is gorgeous and haunting long after one finishes.

Grade: A

Awesome. Now go watch the movie. I'm curious to hear how it does in comparison.

ReplyDelete